Jumpserver is an open-source Privileged Access Management (PAM) tool developed by Fit2Cloud. It's widely used in China and offers a comprehensive suite of features, including SSH, RDP, database, and FTP tunneling using a user-friendly web interface. Acting as a bastion host to an internal network, it offers a centralized point of access and control for accessing internal hosts. But what happens when this gateway itself is compromised?

At SonarSource, we're dedicated to helping developers write secure code. Our vulnerability research team actively analyzes open-source software, identifying and reporting vulnerabilities to improve the security of the ecosystem. In this blog post, we'll delve into the security of Jumpserver, and explore critical vulnerabilities that could allow attackers to bypass authentication and gain complete control of Jumpserver infrastructure.

Some of the findings discussed in these blog posts were first presented at Insomni'hack last year. The recording of the talk Diving Into JumpServer: The Public Key Unlocking Your Whole Network is available on YouTube.

Impact

The centralized nature of JumpServer makes it a critical security asset. If compromised, it can grant attackers access to the entire internal network. Combining our findings could enable unauthenticated attackers to bypass authentication and achieve complete control of the JumpServer system and its underlying infrastructure.

These vulnerabilities were fully addressed in JumpServer versions 3.10.12, 4.0.0 and are tracked as CVE-2023-43650, CVE-2023-43651, CVE-2023-43652, CVE-2023-42818, CVE-2023-46123, CVE-2024-29201, CVE-2024-29202, CVE-2024-40628, CVE-2024-40629.

In this article, we will focus on the authentication bypass vulnerabilities (CVE-2023-43650, CVE-2023-43652, CVE-2023-42818, CVE-2023-46123), which allow attackers to impersonate users and pave the path for exploiting subsequent vulnerabilities that will be covered in the next blog post.

Technical Details

Background

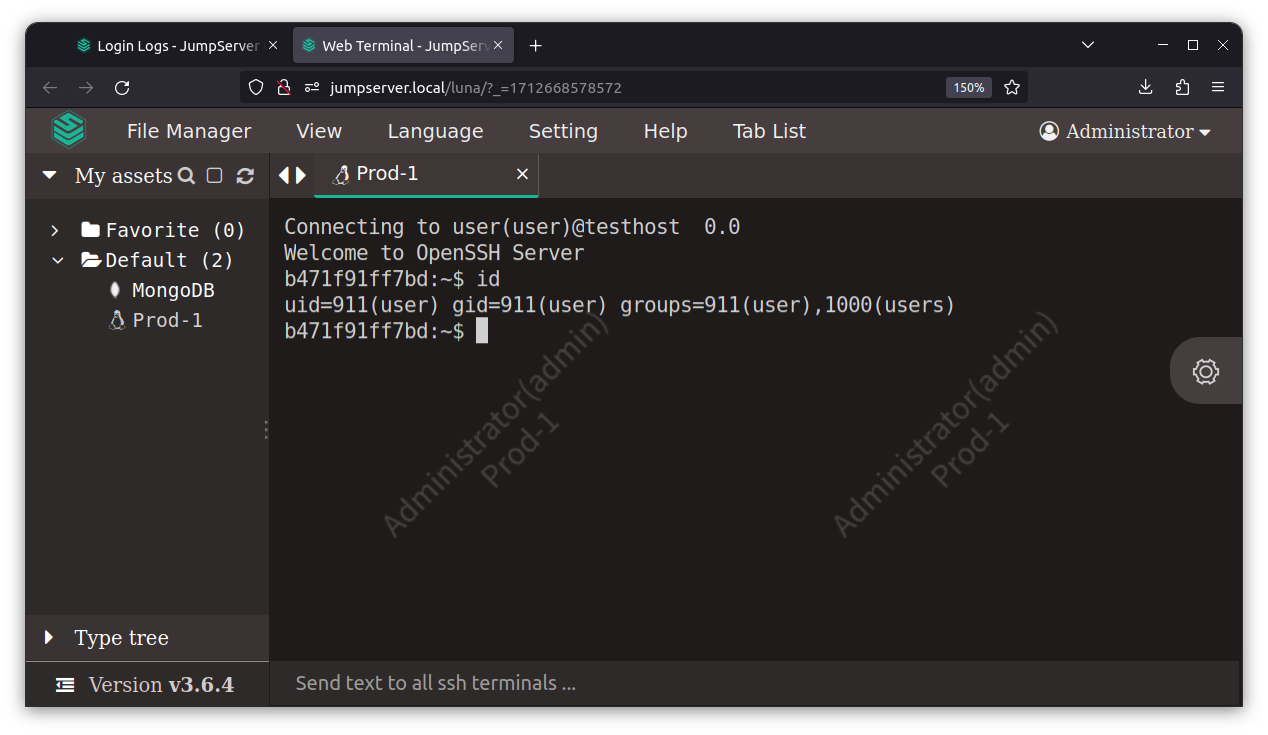

JumpServer provides users with a centralized and user-friendly web interface for accessing various resources within the internal network. This streamlined approach simplifies access management and enhances overall user experience.

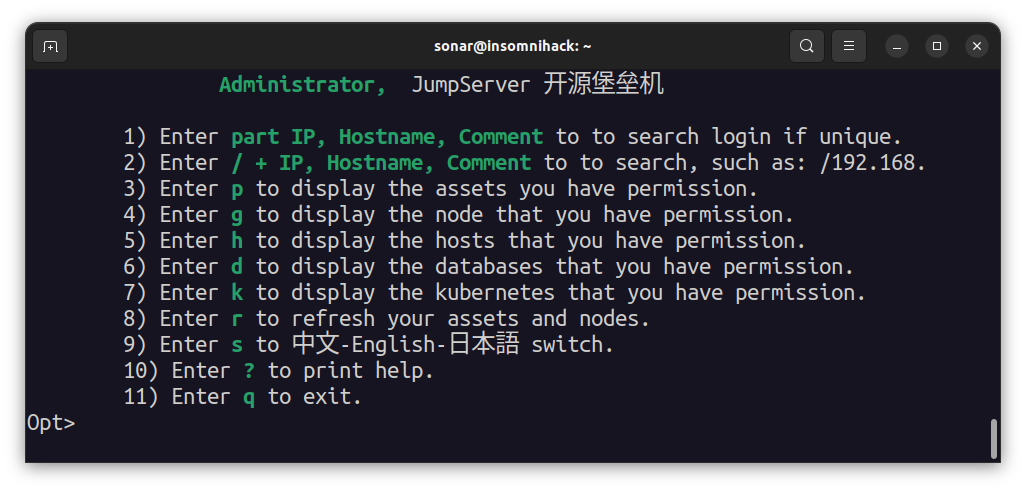

For those who prefer a more traditional approach, JumpServer also supports direct access via SSH clients. This flexibility caters to diverse user preferences and existing workflows.

But before delving into the details of our findings it's essential to first understand the underlying architecture of JumpServer. This knowledge will provide the necessary context for comprehending how these flaws can be exploited to compromise the system and gain unauthorized access to sensitive resources.

Architecture

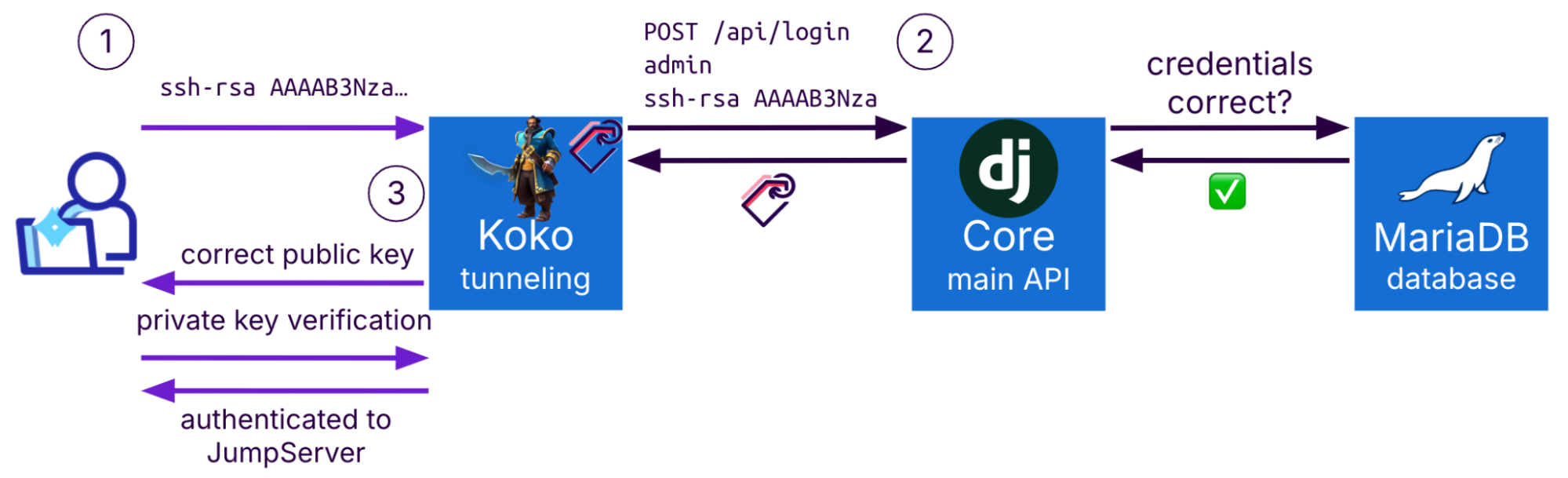

JumpServer, at its core, is built on a microservices architecture. This means it's composed of several independent components that work together to provide its functionality. Each of these components is essentially a Docker container. Here's a breakdown of the key components that will be relevant in this blog series:

- Core (Main API): Written in Python-Django, it serves as the central API, responsible for scheduling tasks, authentication, authorization, and more. This critical component interacts directly with the database microservice to validate user credentials and manage access permissions.

- Database: A critical component storing sensitive information, including user credentials and the credentials of various hosts within the network. This makes it a prime target for attackers, as compromising the database could grant them widespread access and control.

- Koko: Developed in Go, this microservice handles the core tunneling functions, from web terminals, and FTP file explorer to SSH Tunneling that provides direct SSH connections to internal hosts.

- Celery: Named after the popular Python library, it acts as JumpServer's task manager. Celery handles a “task queue” for recurring tasks like connectivity tests and maintains “job scheduling” for custom jobs on hosts.

- Web Proxy: Lastly, the web proxy is the entry point for web-based connections, forwarding requests to the Core API.

To assess potential vulnerabilities from an external attacker's standpoint, we'll first examine Koko and the Web API, as these are the components exposed to external threats.

Authentication

JumpServer offers flexible authentication options, allowing users to authenticate through either the web UI (HTTP) or an SSH client:

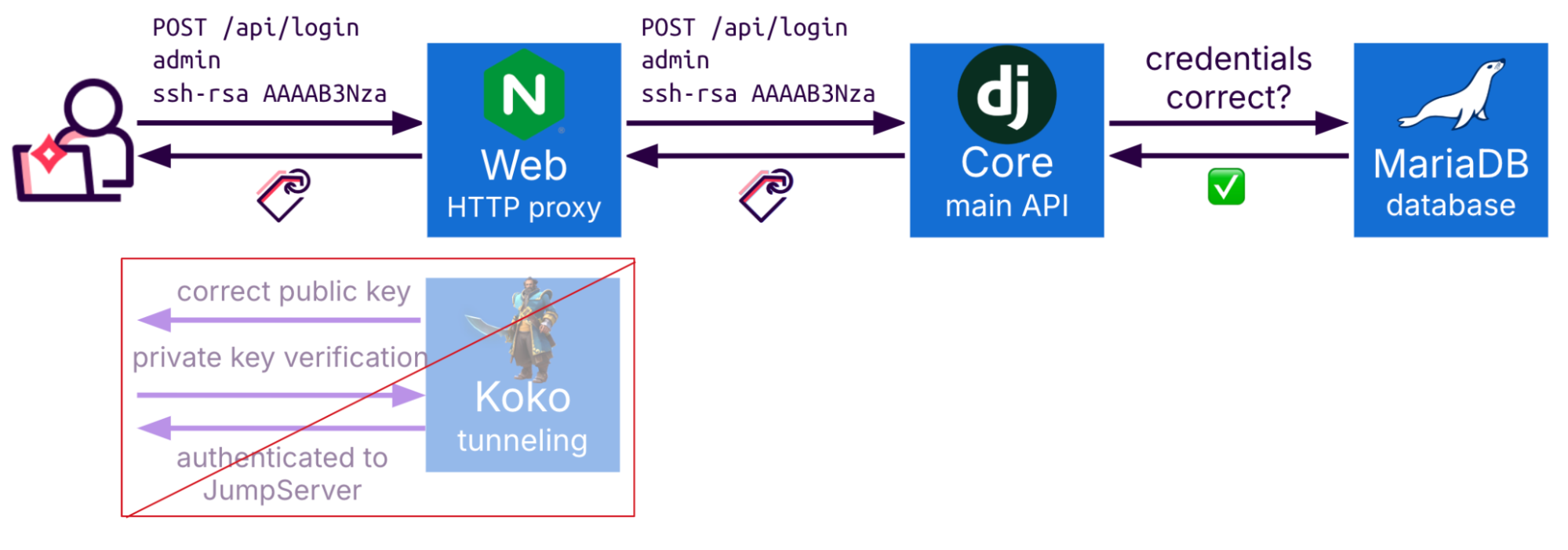

- Web UI employs a conventional authentication flow. When a user attempts to log in, the provided credentials are verified against the database. If the credentials are valid, a session token is generated and sent to the user, granting access to the system.

- SSH Authentication, however, presents a unique challenge, as traditional session tokens aren't readily applicable in this context. JumpServer addresses this through a custom implementation.

When a user connects using an SSH client, the Koko container manages the communication with the client. It essentially acts as an intermediary, taking the user's password credentials and performing the authentication process via the Core API, mirroring the web UI's authentication flow.

Upon successful authentication, the Koko container stores the generated session token and associates it with the user's SSH channel, which allows the container to effectively manage and track the SSH user's session.

But SSH authentication could be performed via asymmetric keys; it’s even the recommended method. How does Koko handle this type of authentication?

First, by receiving the public key from the user, and then obtaining a session key from the core API. After Koko receives the token it knows that a user with such a public key exists and continues to perform key validation directly with the user.

Authentication Bypass (CVE-2023-43652)

You might have already noticed a red flag in this mechanism, the Core API provides a valid session token to Koko only by providing a public key.

Considering the microservice architecture of JumpServer we know that there is another way of accessing the core API, and that is through the nginx HTTP interface. Looking and the code when JumpServer tries to authenticate the user using a public key, there is no verification that the request is performed from the Koko service:

def authenticate(self, request, username=None, public_key=None, **kwargs):

if not public_key:

return None

if username is None:

username = kwargs.get(UserModel.USERNAME_FIELD)

try:

user = UserModel._default_manager.get_by_natural_key(username)

except UserModel.DoesNotExist:

return None

else:

if user.check_public_key(public_key) and \

self.user_can_authenticate(user):

return userAn attacker can execute the same request directly using the HTTP interface, essentially impersonating the Koko container without requiring any key validation.

Obtaining a user’s public keys isn’t a complicated task; as the name suggests, they are public. For demonstration purposes, you can go to any GitHub user profile, simply add .keys to the URL, and see their public keys.

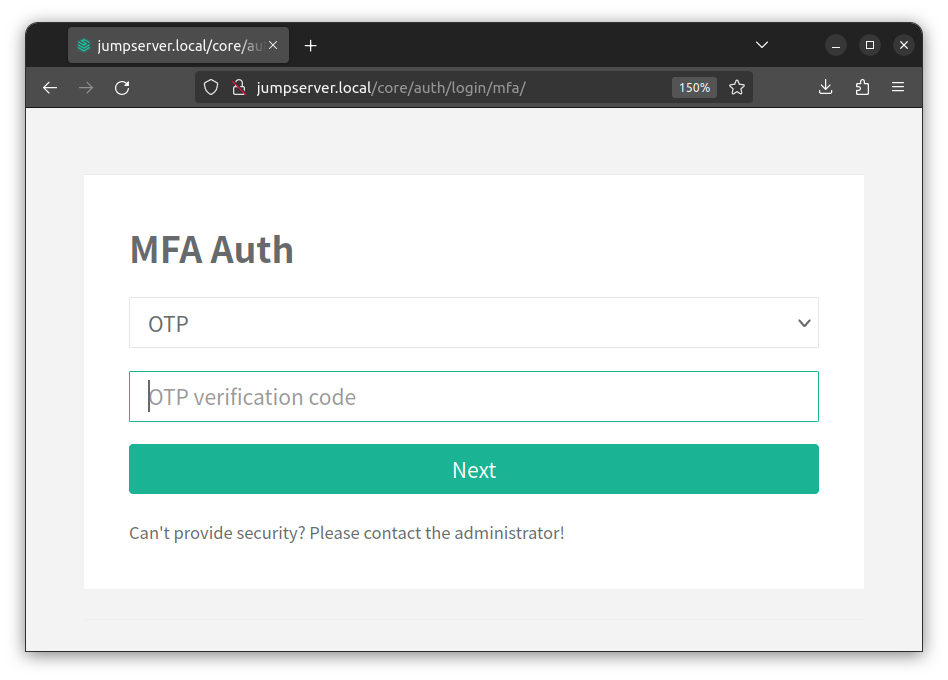

MFA bypass (CVE-2023-46123), or Step 2

Attackers who try to exploit the public key authentication bypass might face another obstacle in case the victim account enabled Multi-factor authentication (MFA).

Similar to authentication, implementing such a feature is less obvious in the SSH context than on the web. So, how does it work under the hood in Jumpsever?

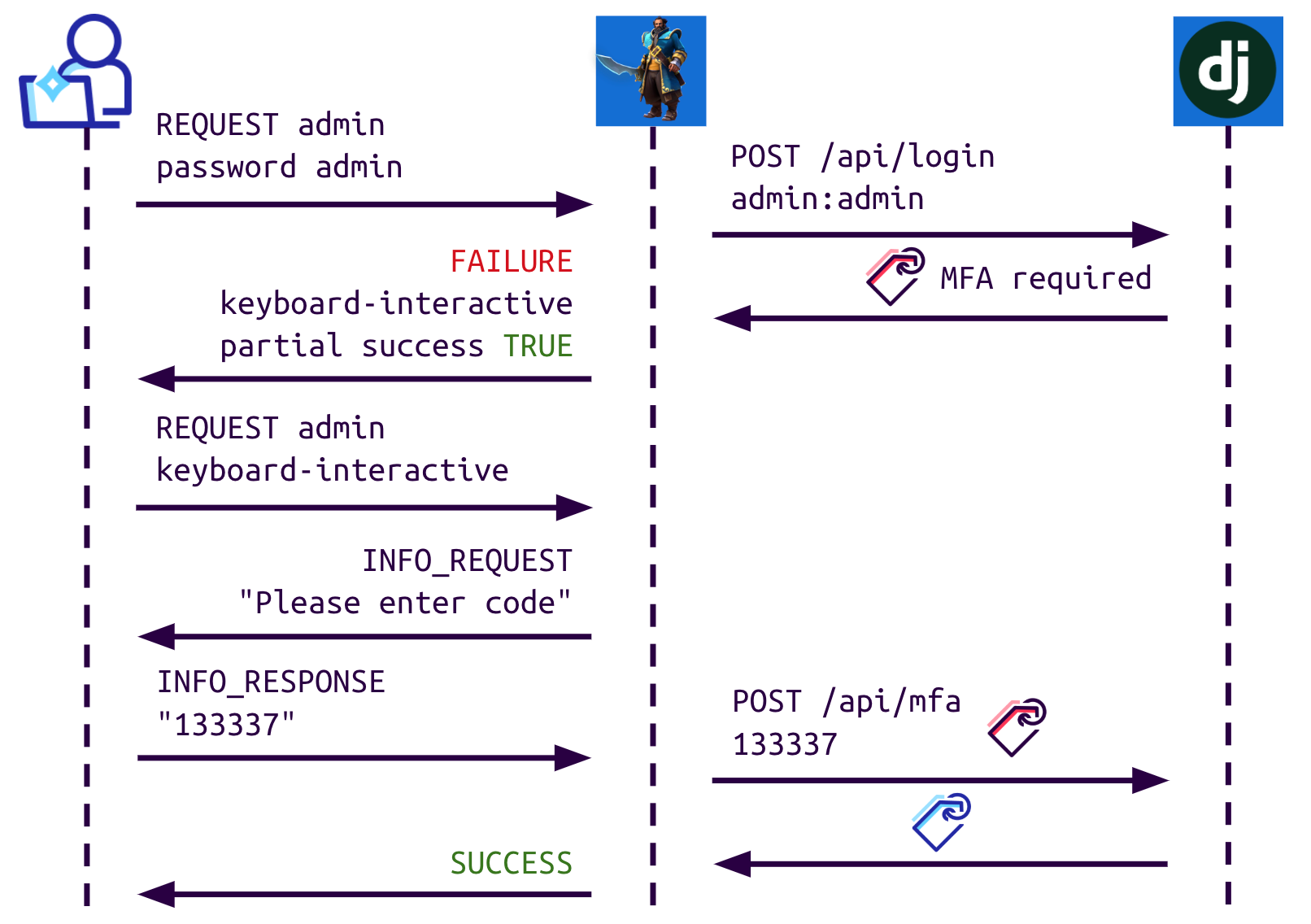

In the SSH protocol, the server maintains a list of supported authentication methods, such as public key, password, host-based, and keyboard-interactive. When the client attempts to connect, the server shares this list, and the client must choose one of the available methods to authenticate. After the authentication is successful a “SUCCESS” message is sent, starting the SSH session.

To implement MFA, the SSH protocol also supports a “partial success” message, saying to the user that although the authentication was correct there is a need for an additional step. Here, it could change to the “keyboard-interactive” type to allow the client to enter the MFA code.

As mentioned before, Jumpserver tunnels SSH sessions and needs to implement certain things in order to support MFA. A successful two-factor authentication would look like this:

One of the common ways attackers bypass TOTP-based MFA is by brute force. If the application fails to implement a prevention mechanism, attackers could simply try every possible TOTP code as it is only a 6-digit string. But trying to do so in Jumpserver would result in a rate-limiting response pretty quickly.

Rate-limiting verification is often done by checking the number of requests made by an IP address, but since everything is centralized in the core API, Jumpserver forwards the client’s IP taken from the SSH connection as an extra parameter in the /api/mfa request:

POST /api/mfa

{

"code": "133337",

"remote_addr": "12.34.56.78"

}In a similar fashion to the previous vulnerability, There is no verification that this request is made from the Koko container:

def get_request_ip(self):

ip = ''

if hasattr(self.request, 'data'):

ip = self.request.data.get('remote_addr', '')

ip = ip or get_request_ip(self.request)

return ipAn attacker can directly call the core API via the web proxy, changing the remote_addr parameter every time and bypassing the rate-limiting mechanism. This rate-limiting bypass also allows attackers to brute-force the passwords themselves via a different endpoint.

Additionally, other vulnerabilities such as lack of rate limiting on the password reset (CVE-2023-43650) and bypassing a partial success false response using public SSH key and custom client (CVE-2023-42818) were discovered and disclosed by Sonar.

Patch

The vulnerabilities discussed here were fixed in various ways and versions:

- CVE-2023-43650: fixed in versions 2.28.20 and 3.7.1 by adding a 3-tries rate limit

- CVE-2023-43652: fixed in versions 2.28.20 and 3.7.1 by separating the public key authentication API from token generation and only providing it to Koko for verification.

- CVE-2023-42818: fixed in versions >= 3.7.2 by introducing a state tracking mechanism for partial success through the

SSHAuthLogCallbackcode. Without theCONTEXT_PARTIAL_SUCCESS_METHOD, the second authentication stage will be denied. - CVE-2023-46123: fixed in versions >= 3.8.0, by trusting only the

remote_addrparameter if it originates from Koko using a signature.

Organizations relying on JumpServer should ensure they are running the latest patched versions, which were fully addressed in JumpServer versions 3.10.12 and 4.0.0.

Timeline

| Date | Action |

| 2023-09-18 | We report our initial discoveries to JumpServer |

| 2023-09-25 | Fit2Cloud confirms the issues |

| 2023-09-27 | Fit2Cloud releases versions 2.28.20 and 3.7.1 addressing CVE-2023-43650 and CVE-2023-43652 |

| 2023-10-05 | We send a follow-up report with additional findings |

| 2023-10-05 | Fit2Cloud confirms the issues |

| 2023-10-23 | Fit2Cloud releases version 3.7.2 addressing CVE-2023-42818 |

| 2023-10-24 | Fit2Cloud releases version 3.8.0 addressing CVE-2023-46123 |

Summary

In this blog post, we explore security flaws that primarily originate from architectural mistakes. Specifically, we highlight the risks associated with inadequate microservice isolation, where unintended cross-service interactions can lead to significant security implications. The vulnerabilities underscore the importance of secure coding practices, thorough testing, threat modeling, and continuous security assessments. By understanding the root causes of these vulnerabilities, developers can learn to build more secure systems and protect against similar attacks.

We would like to thank Fit2Cloud for their responsiveness in addressing these issues and for their commitment to security. We also acknowledge the contributions of other researchers, specifically Ethan Yang, Hui Song, pokerstarxy, Lawliet and Zhiniang Peng, whose findings paved the way for our own discoveries.